Historically, the field of computer science (CS) has maintained a low level of representation for women and ethnic minorities. Culturally relevant pedagogy (CRP) is an approach that has been developed to address this. It focuses on social equity and justice, and has been used in CS to develop engaging and responsive computing teaching for students regardless of their social background. Much of the research relating to CRP has taken place in the US, which reveals a gap in how this pedagogy might be used in the context of the UK.

Our project

In 2022, we were fortunate enough to be funded by Google to conduct research in schools in England relating to the ways in which teachers might approach culturally responsive computing teaching. In England, computing is a mandatory subject from 5-16 years old, although in reality provision for all stops at age 14 when young people choose their GCSEs (qualifications for 14-16 year old students). Having conducted a project in 2021 which led to a booklet giving guidance on how to develop CRP in computing, this project sought to investigate what this might look like in practice. The idea of the project was to work with a small number of teachers in collaboration, and to gather qualitative data that would help us to understand the ways in which teaching in computing could become more culturally responsive. The technical report describing the project is shared on this website and we have written two academic papers which will be published later this year.

10 Areas of Opportunity

As part of this project, we developed a framework of ten ‘Areas of Opportunity’ that teachers might find helpful to consider when deciding how their practice was already or could become culturally responsive. We used this framework in the workshops that we carried out in schools participating in the project. The Areas of Opportunities are shown below.

| # | Area of Opportunity | Description |

| 1 | Learners | Find out about learners in order to reveal opportunities to adapt our teaching |

| 2 | Teachers | Find out about ourselves as practitioners – to reflect on one’s cultural lens |

| 3 | Content | Review what is taught and add in extra culturally relevant content (e.g., about social justice/ethics, data bias accessibility etc.) |

| 4 | Context | Review contexts and examples used – to make teaching relevant, meaningful, to contextualise and make connections |

| 5 | Accessibility | Make the content accessible and relevant |

| 6 | Activity | Provide opportunities for learners to think about user experience and alternate viewpoints, participate in open-ended, inquiry led, or problem-solving activities. |

| 7 | Collaboration | Develop student oriented learning through collaboration and structured group discussion |

| 8 | Student Agency | Develop student oriented learning through student choice |

| 9 | Materials | Review the learning environment (including learning materials) – to increase accessibility, a sense of belonging and promote respect |

| 10 | Policy | Review related policies, process and training in your school and department |

The research was primarily centred around two workshops held in schools with participating teachers. We initially recruited 26 teachers to the study; however with some attrition, we worked with 8 schools and 17 teachers to the end of the project.

The Workshops

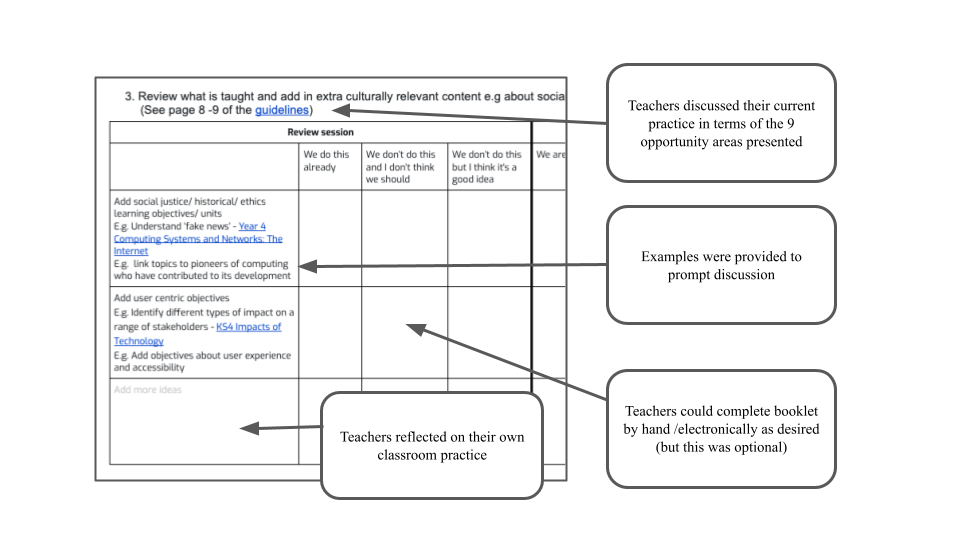

The two workshops were held at individual schools, where researchers met with teachers to discuss culturally responsive computing teaching. During the first workshop, teachers worked with researchers to reflect on their current practice using the framework and planned small interventions for their classroom teaching over the coming months. The image below shows an extract from a booklet we developed to frame the conversation, structured around the 10 Areas of Opportunity. Initial conversations with teachers revealed that once they started to reflect on their current practice, there were already many ways in which they were already incorporating some aspects of culturally relevant pedagogy into their computing lessons.

Teachers then planned where they might be able to ‘tweak’ their lessons in the coming months as an intervention. No particular approaches were prescribed by the researchers. Teachers were invited to look at what was coming up in their schemes of work, and topics that they would be covering, and see how lessons could be adapted, using the Areas of Opportunity as prompts.

What did we find?

We collected data from workshops, booklets and various artefacts used in discussion with teachers. We found that in Workshop 1, before the intervention, the most common theme emerging was the way that all of the teachers in our study were developing a rapport with individual learners and using what they learned to make their lessons contextually relevant. For example, teachers might engage learners in discussions about what they were interested in outside school so that they could relate it to the lesson.

After the intervention, one of the main findings was that many of the teachers reported that they had developed student agency or choice as a way of making computing more relevant to them in terms. Student agency involves giving learners more choices in their learning, and empowering them to engage with computing in a way that is meaningful to them. Examples emerging from the study included physical computing lessons where pupils decided what they wanted to make, and being encouraged to express themselves and their identity in creative media projects. Having more agency in learning can build confidence in learners as well as making the subject feel more relevant to their own context.

Writing in the US, Madkins, Howard and Freed, in their article Engaging Equity Pedagogies in Computer Science Learning Environments , describe how teachers can position students as creative agents or change agents by adapting lessons as follows:

- “Empower learners to become creative innovators with technology, able to repurpose technology towards their own goals.

- Build enough flexibility into both the tools and the activities to leave room for students to pursue goals that are meaningful to them.

- Legitimize student expertise through creating opportunities to share their work with the broader community and/or making their work visible in a shared space.” (page 14)

Another way in which nearly all teachers had been able to tweak their lessons was to deliver computing topics within a context that was relevant to the children, for example, relating it to something else they were learning in another subject in school, or to topics relating to youth culture. Other teachers reported making changes to the classroom environment and the amount of collaboration between students. In addition, teachers reported being more reflexive about their own practice: reflecting on their practice and subsequently putting changes in place.

Moving forward

Our analysis of the experience of teachers has led us to four ‘themes’ that could be used to understand culturally relevant computing in the classroom – these move us on from the Areas of Opportunity to a deeper understanding of dimensions of change that could make classroom practice more culturally responsive in computing. These are, in no particular order:

- Providing relevant context and content

- Establishment of rapport and confidence building

- Integration of social justice concepts (e.g., data bias, ethics of emerging technologies) into the computing education curriculum

- Multi-level review of practice

Themes A and B involve the learner’s context, culture and background, and what the teacher can do to support the development of digital cultural capital. Themes C and D are about the need for computing education to actively strive for a more socially just world, and value dialogue, discussion and questioning. Through theme C, pupils and teachers are encouraged to both consciously attend to social injustice that might be brought about through use of technology, and embrace computing as a tool for advancing equity and freedom in the world. Theme D relates to the ways in which teachers and schools can actively critique their practice and pedagogy, and the impact it has on making computing more diverse and inclusive. Our initial findings point to the fact that themes A, B and D were more prevalent than C (integration of social justice concepts); as yet we don’t know if that is a generalisable finding and whether it might be related to the prescribed curriculum / school ethos.

We write about these themes in much more detail in a paper that will be published (open-access) at the ICER conference in August and more succinctly in our technical report summarising the project. Do take a look at both (we’ll share the paper here when it’s published). If you’re a teacher reading this, and you use our research to review your practice and implement small changes using the Areas of Opportunity, we’d love to hear from you! Email us and let us know how you got on.

Many thanks to all the teachers (all anonymous!) who participated in this project, and to the team of researchers and coordinators who worked on it in various capacities at points during the year: Polly Card, Katharine Childs, Lynda Chinaka, Anjali Das, Alyson Hwang, Bonnie Sheppard and Jane Waite. We all learned a lot, and are keen to explore this topic more.